In August 1766, the Royal Navy frigate HMS Dolphin set sail under the command of Samuel Wallis, on her second journey of discovery and circumnavigation. Following victory in the Seven Years’ War, three years earlier, the Royal Navy hierarchy decided to explore the Pacific Ocean in order to develop new trade routes and possibly find a new route to the all-important East Indies. Hence Commodore John Byron’s journey of circumnavigation, on the Dolphin, which was the first to be completed in less than two years.

In August 1766, the Royal Navy frigate HMS Dolphin set sail under the command of Samuel Wallis, on her second journey of discovery and circumnavigation. Following victory in the Seven Years’ War, three years earlier, the Royal Navy hierarchy decided to explore the Pacific Ocean in order to develop new trade routes and possibly find a new route to the all-important East Indies. Hence Commodore John Byron’s journey of circumnavigation, on the Dolphin, which was the first to be completed in less than two years.

In Dolphin, Wallis knew he had a ship that was up to the task; however, he would be accompanied on his voyage by HMS Swallow, a sloop that was far from ship-shape, under the command of Philip Carteret. The two ships became separated after sailing through perilous Straits of Magellan. In spite of the decrepit condition of his craft, Carteret managed to complete his mission arriving back in England three years after setting sail, having discovered various new landmasses including Pitcairn Island and a series of atolls that now bear his name.

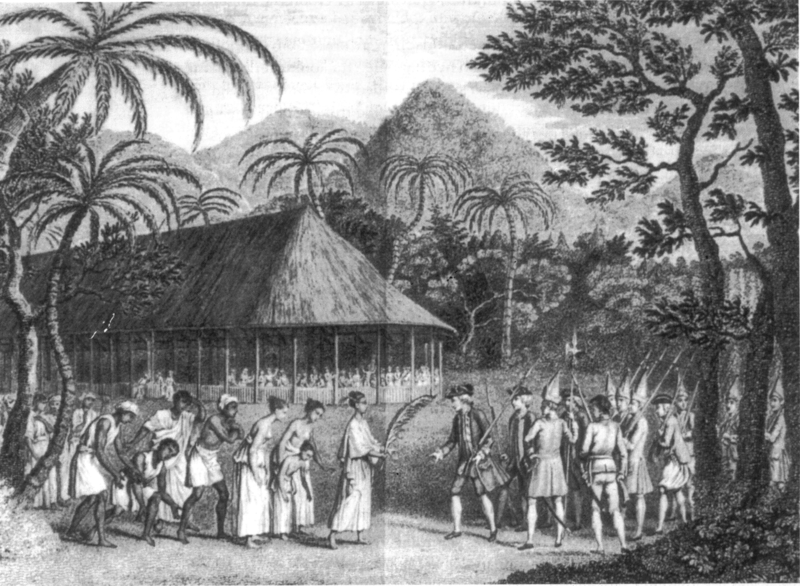

After losing contact with the Swallow, Wallis directed his crew to sail across the South Pacific; but scurvy and ill favoured winds forced him to head northwards. In the warmer seas he also discovered a number of islands then unknown to Europeans and on 18th June 1767 he sighted Tahiti, where the Dolphin and her crew remained for the next five weeks. In the first few days saw sporadic attacks by Tahitians on the crew, but these stopped after many locals were injured or killed by cannon fire.

Wallis could do little to quell the disturbances because he had been stricken with fever even as the health of his men improved. Indeed, when the Dolphin returned to England in May 1768, her commander’s health was still in a poor state in spite of his efforts to maintain the health of his crew by using a three shift rotation so that the sailors could have more rest, maintaining stores of fruit and vegetables, and by keeping clothes and bedding as clean and dry as possible – innovations that were all used by the famous Captain Cook during his voyages of exploration.

To learn more about the voyages of Byron, Cateret, Wallis and Cook the National Library of Australia’s web site hosts a hypertext version of John Hawkesworth (Ed.), Account of the Voyages … in the Southern Hemisphere (London, 1773), Vol 1 and Vol 2 & 3